" Julieta begins. But Bobby cuts her off: "You got what

you wanted and then some. A British passport and " glancing out the window

he sees the doctor emerging from the courthouse " Enoch's survivor's

benefits on top of it. And maybe more later. As for you, Otto, your career

as a smuggler is over. I suggest you get the fuck out of here."

Otto's still too flabbergasted to be outraged, but he's sure enough

gonna be outraged pretty soon. "And go where!? Have you bothered to look at

a map?"

"Display some fucking adaptability," Shaftoe says. "You can figure out

a way to get that tub of yours to England."

Say what you will about Otto, he likes a challenge. "I could traverse

the Göta Canal from Stockholm to Göteborg no Germans there that would get me

almost to Norway but Norway's full of Germans! Even if I make it through the

Skagerrak you expect me to cross the North Sea? In winter? During a war?"

"If it makes you feel any better, after you get to England you have to

sail to Manila."

"Manila!?"

"Makes England seem easy, huh?"

"You think I am a rich yachtsman, who sails around the world for fun!?"

"No, but Rudolf von Hacklheber is. He's got money, he's got

connections. He's got a line on a good yacht that makes your ketch look like

a dinghy," Shaftoe says. "C'mon, Otto. Stop whining, pull some more diamonds

out of your asshole, and get it done. It beats being tortured to death by

Germans." Shaftoe stands up and chucks Otto encouragingly on the shoulder,

which Otto does not like at all. "See you in Manila."

The doctor's coming in the door. Bobby Shaftoe slaps some money down on

the table. He looks Julieta in the eye. "Got some miles to cover now," he

says, "Glory's waiting for me."

Julieta nods. So in the eyes of one Finnish girl, anyway, Shaftoe's not

such a bad guy. He bends over and gives her a big succulent kiss, then

straightens up, nods to the startled doctor, and walks out.

Chapter 61 COURTING

Waterhouse has been chewing his way through exotic Nip code systems at

the rate of about one a week, but after he sees Mary Smith in the parlor of

Mrs. McTeague's boarding house, his production rate drops to near zero.

Arguably, it goes negative, for sometimes when he reads the morning

newspaper, its plaintext scrambles into gibberish before his eyes, and he is

unable to extract any useful information.

Despite his and Turing's disagreements about whether the human brain is

a Turing machine, he has to admit that Turing wouldn't have too much trouble

writing a set of instructions to simulate the brain functions of Lawrence

Pritchard Waterhouse.

Waterhouse seeks happiness. He achieves it by breaking Nip code systems

and playing the pipe organ. But since pipe organs are in short supply, his

happiness level ends up being totally dependent on breaking codes.

He cannot break codes (hence, cannot be happy) unless his mind is

clear. Now suppose that mental clarity is designated by C [sub m], which is

normalized, or calibrated, in such a way that it is always the case that

0 <= C [sub m] < 1

where C [sub m] = 0 indicates a totally clouded mind and C [sub m] = 1

is Godlike clarity an unattainable divine state of infinite intelligence. If

the number of messages Waterhouse decrypts, in a given day, is designated by

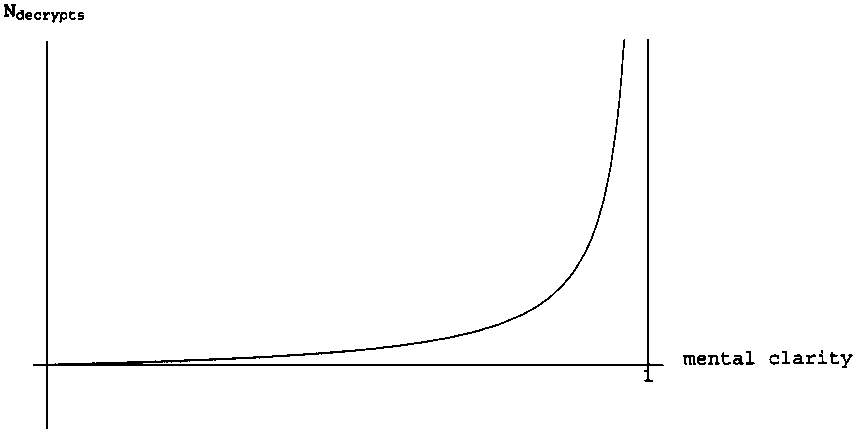

then it will be governed by C [sub m] in roughly the following way:

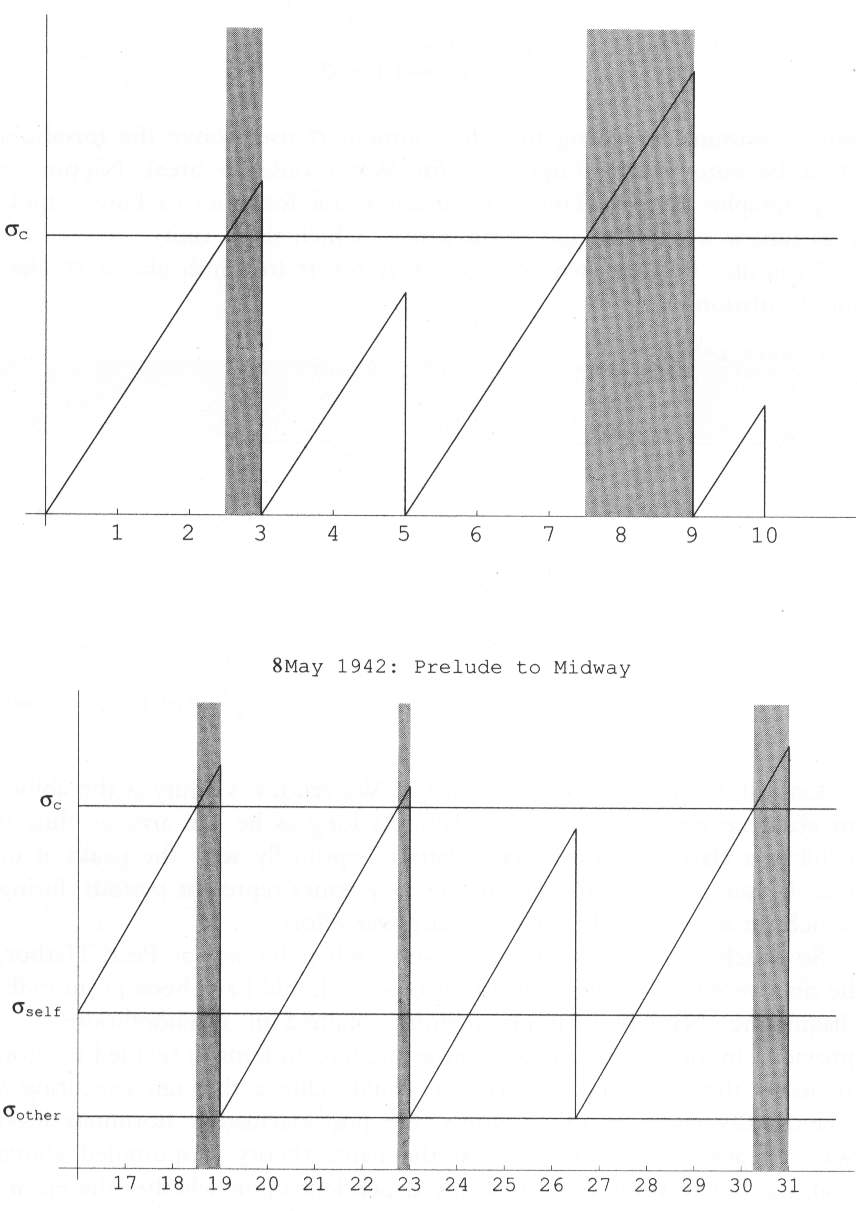

Clarity of mind (C [sub m]) is affected by any number of factors, but

by far the most important is horniness, which might be designated by

[sigma], for obvious anatomical reasons that Waterhouse finds amusing at

this stage of his emotional development.

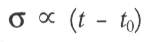

Horniness begins at zero at time t = t [sub 0] (immediately following

ejaculation) and increases from there as a linear function of time:

Clarity of mind (C [sub m]) is affected by any number of factors, but

by far the most important is horniness, which might be designated by

[sigma], for obvious anatomical reasons that Waterhouse finds amusing at

this stage of his emotional development.

Horniness begins at zero at time t = t [sub 0] (immediately following

ejaculation) and increases from there as a linear function of time:

The only way to drop it back to zero is to arrange another ejaculation.

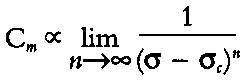

There is a critical threshold [sigma sub c] such that when [sigma] >

[sigma sub c] it becomes impossible for Waterhouse to concentrate on

anything, or, approximately,

The only way to drop it back to zero is to arrange another ejaculation.

There is a critical threshold [sigma sub c] such that when [sigma] >

[sigma sub c] it becomes impossible for Waterhouse to concentrate on

anything, or, approximately,

which amounts to saying that the moment [sigma] rises above the

threshold [sigma sub c] it becomes totally impossible for Waterhouse to

break Nipponese cryptographic systems. This makes it impossible for him to

achieve happiness (unless there is a pipe organ handy, which there isn't).

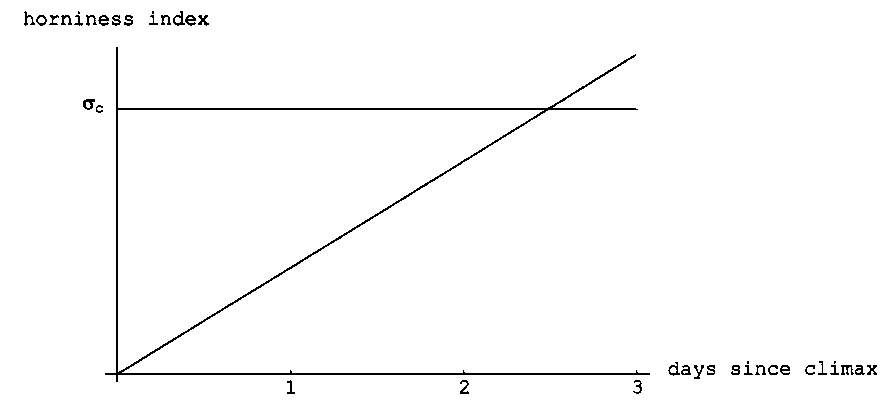

Typically, it takes two to three days for [sigma] to climb above [sigma

sub c] after an ejaculation:

which amounts to saying that the moment [sigma] rises above the

threshold [sigma sub c] it becomes totally impossible for Waterhouse to

break Nipponese cryptographic systems. This makes it impossible for him to

achieve happiness (unless there is a pipe organ handy, which there isn't).

Typically, it takes two to three days for [sigma] to climb above [sigma

sub c] after an ejaculation:

Critical, then, to the maintenance of Waterhouse's sanity is the

ability to ejaculate every two to three days. As long as he can arrange

this, [sigma] exhibits a classic sawtooth wave pattern, optimally with the

peaks at or near [sigma sub c] [see p. 546 top] wherein the grey zones

represent periods during which he is completely useless to the war effort.

So much for the basic theory. Now, when he was at Pearl Harbor, he

discovered something that, in retrospect, should have been profoundly

disquieting. Namely, that ejaculations obtained in a whorehouse (i.e.,

provided by the ministrations of an actual human female) seemed to drop

[sigma] below the level that Waterhouse could achieve through executing a

Manual Override. In other words, the post ejaculatory horniness level was

not always equal to zero, as the naive theory propounded above assumes, but

to some other quantity dependent upon whether the ejaculation was induced by

Self or Other: [sigma] =[sigma sub self] after masturbation but

[sigma]=[sigma sub other] upon leaving a whorehouse, where [sigma sub self]

> [sigma sub other] an inequality to which Waterhouse's notable successes

in breaking certain Nip naval codes at Station Hypo were directly

attributable, in that the many convenient whorehouses nearby made it

possible for him to go somewhat longer between ejaculations.

Critical, then, to the maintenance of Waterhouse's sanity is the

ability to ejaculate every two to three days. As long as he can arrange

this, [sigma] exhibits a classic sawtooth wave pattern, optimally with the

peaks at or near [sigma sub c] [see p. 546 top] wherein the grey zones

represent periods during which he is completely useless to the war effort.

So much for the basic theory. Now, when he was at Pearl Harbor, he

discovered something that, in retrospect, should have been profoundly

disquieting. Namely, that ejaculations obtained in a whorehouse (i.e.,

provided by the ministrations of an actual human female) seemed to drop

[sigma] below the level that Waterhouse could achieve through executing a

Manual Override. In other words, the post ejaculatory horniness level was

not always equal to zero, as the naive theory propounded above assumes, but

to some other quantity dependent upon whether the ejaculation was induced by

Self or Other: [sigma] =[sigma sub self] after masturbation but

[sigma]=[sigma sub other] upon leaving a whorehouse, where [sigma sub self]

> [sigma sub other] an inequality to which Waterhouse's notable successes

in breaking certain Nip naval codes at Station Hypo were directly

attributable, in that the many convenient whorehouses nearby made it

possible for him to go somewhat longer between ejaculations.

Note the twelve day period [above], 19 30 May 1942, with only one brief

interruption in productivity during which Waterhouse (some might argue)

personally won the Battle of Midway.

If he had thought about this, it would have bothered him, because

[sigma sub self] > [sigma sub other] has troubling implications

particularly if the values of these quantities w.r.t. the all important

[sigma sub c] are not fixed. If it weren't for this inequality, then

Waterhouse could function as a totally self contained and independent unit.

But [sigma sub self] > [sigma sub other] implies that he is, in the long

run, dependent on other human beings for his mental clarity and, therefore,

his happiness. What a pain in the ass!

Perhaps he has avoided thinking about this precisely because it is so

troubling. The week after he meets Mary Smith, he realizes that he is going

to have to think about it a lot more.

Something about the arrival of Mary Smith on the scene has completely

fouled up the whole system of equations. Now, when he has an ejaculation,

his clarity of mind does not take the upwards jump that it should. He goes

right back to thinking about Mary. So much for winning the war!

He goes out in search of whorehouses, hoping that good old reliable

[sigma sub other] will save his bacon. This is troublesome. When he was at

Pearl, it was easy, and uncontroversial. But Mrs. McTeague's boardinghouse

is in a residential neighborhood, which, if it contains whorehouses, at

least bothers to hide them. So Waterhouse has to travel downtown, which is

not that easy in a place where internal combustion vehicles are fueled by

barbecues in the trunk. Furthermore Mrs. McTeague is keeping her eye on him.

She knows his habits. If he starts coming back from work four hours late, or

going out after dinner, he'll have some explaining to do. And it had better

be convincing, because she appears to have taken Mary Smith under one

quivering gelatinous wing and is in a position to poison the sweet girl's

mind against Waterhouse. Not only that, he has to do much of his excuse

making in public, at the dinner table, which he shares with Mary's cousin

(whose first name turns out to be Rod).

But hey, Doolittle bombed Tokyo, didn't he? Waterhouse should at least

be able to sneak out to a whorehouse. It takes a week of preparations

(during which he is completely unable to accomplish meaningful work because

of the soaring [sigma] level), but he manages it.

It helps a little, but only on the [sigma] management level. Until

recently, that was the only level and so it would have been fine. But now

(as Waterhouse realizes through long contemplation during the hours when he

should be breaking codes) a new factor has entered the system of equations

that governs his behavior; he will have to write to Alan and tell him that

some new instructions will have to be added to the Waterhouse simulation

Turing machine. This new factor is F [sub MSp], the Factor of Mary Smith

Proximity.

In a simpler universe, F [sub MSp], would be orthogonal to [sigma],

which is to say that the two factors would be entirely independent of each

other. If it were thus, Waterhouse could continue the usual sawtooth wave

ejaculation management program with no changes. In addition, he would have

to arrange to have frequent conversations with Mary Smith so that F [sub

MSp] would remain as high as possible.

Alas! The universe is not simple. Far from being orthogonal, F [sub

MSp] and [sigma] are involved, as elaborately as the contrails of

dogfighting airplanes.

The old [sigma] management scheme doesn't work anymore. And a platonic

relationship will actually make F [sub MSp] worse, not better. His life,

which used to be a straightforward set of basically linear equations, has

become a differential equation.

It is the visit to the whorehouse that makes him realize this. In the

Navy, going to a whorehouse is about as controversial as pissing down the

scuppers when you are on the high seas the worst you can say about it is

that, in other circumstances, it might seem uncouth. So Waterhouse has been

doing it for years without feeling troubled in the slightest.

But he loathes himself during, and after, his first post Mary Smith

whorehouse visit. He no longer sees himself through his own eyes but through

hers and, by extension, those of her cousin Rod and of Mrs. McTeague and of

the whole society of decent God fearing folk to whom he has never paid the

slightest bit of attention until now.

It seems that the intrusion of F [sub MSp] into his happiness equation

is just the thin edge of a wedge which leaves Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse

at the mercy of a vast number of uncontrollable factors, and requiring him

to cope with normal human society. Horrifyingly, he now finds himself

getting ready to go to a dance.

The dance is being organized by an Australian volunteer organization he

doesn't know or care about the details. Mrs. McTeague evidently feels that

the rent she collects from her boarders obligates her to find them wives as

well as feeding and housing them, so she badgers all of them to go, and to

bring dates if possible. Rod finally shuts her up by announcing that he will

be attending with a large group, to include his country cousin Mary. Rod is

about eight feet tall, and so it will be easy to pick him out across a

crowded dance floor. With any luck, then, the diminutive Mary will be in his

vicinity.

So Waterhouse goes to the dance, ransacking his mind for opening lines

that he can use with Mary. He comes up with several possibilities:

"Do you realize that Nipponese industry is only capable of producing

forty bulldozers per year?" To be followed up with: "No wonder they use

slave labor to build their revetments!"

Or, "Because of antenna configuration limitations inherent in their

design, Nipponese naval radar systems have a blind spot to the rear you

always want to come in from dead astern."

Or, "The Nip Army's minor, low level codes are actually harder to break

than the important high level ones! Isn't that ironic?"

Or, "So, you're from the outback ... do you can a lot of your own food?

It might interest you to know that a close relative of the bacterium that

makes canned soup go bad is responsible for gas gangrene."

Or, "Nip battleships have started to blow up spontaneously, because the

high explosive shells in their magazines become chemically unstable over

time."

Or, "Dr. Turing of Cambridge says that the soul is an illusion and that

all that defines us as human beings can be reduced to a series of mechanical

operations."

And much more in this vein. So far he has not hit on anything that is

absolutely guaranteed to sweep her off her feet. He doesn't, in fact, have

the first idea what the fuck he's going to do. Which is how it's always been

with Waterhouse and women, which is why he has never really had a girlfriend

before.

But this is different. This is desperation.

What is there to say about the dance? Big room. Men in uniforms, mostly

looking smarter than they have a right to. Mostly looking smarter, in fact,

than Waterhouse. Women in dresses and hairdos. Lipstick, pearls, a big band,

white gloves, fist fights, a little bit o' kissin' and a wee bit o'

vomitin'. Waterhouse gets there late that transportation thing again. All

the gasoline is being used to hurl enormous bombers through the atmosphere

so that high explosives can be showered on Nips. Moving the wad of flesh

called Waterhouse across Brisbane so he can try to deflower a maiden is way

down the priority list. He has to do a lot of walking in his stiff, shiny

leather shoes, which become less shiny. By the time he gets there, he is

pretty sure that they are functioning only as tourniquets preventing

uncontrollable arterial bleeding from the wounds they've induced.

Rather late into the dance he finally picks out Rod on the dance floor

and stalks him, over the course of several numbers (Rod having no shortage

of dance partners), to a corner of the room where everyone seems to know

each other, and all of them seem to be having a perfectly fine time without

the intervention of a Waterhouse.

But finally he identifies Mary Smith's neck, which looks just as

unspeakably erotic seen from behind through thirty yards of dense cigarette

smoke as it did seen from the side in Mrs. McTeague's parlor. She is wearing

a dress, and a string of pearls that adorn the neck's architecture quite

nicely. Waterhouse sets his direction of march towards her and plods onward,

like a Marine covering the last few yards to a Nip pillbox where he knows

full well he's going to die. Can you get a posthumous decoration for being

shot down in flames at a dance?

He's just a few paces away, still forging along woozily towards that

white column of neck, when suddenly the tune comes to an end, and he can

hear Mary's voice, and the voices of her friends. They are chattering away

happily. But they are not speaking English.

Finally, Waterhouse places that accent. Not only that: he solves

another mystery, having to do with some incoming mail he has seen at Mrs.

McTeague's house, addressed to someone named cCmndhd.

It's like this: Rod and Mary are Qwghlmian! And their family name is

not Smith it just sounds vaguely like Smith. It's really cCmndhd. Rod grew

up in Manchester in some Qwghlmian ghetto, no doubt and Mary's from a branch

of the family that got into trouble (probably sedition) a couple of

generations back and got Transported to the Great Sandy Desert.

Let's see Turing explain this one! Because what this proves, beyond all

doubt, is that there is a God, and furthermore that He is a personal friend

and supporter of Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse. The opening line problem is

solved, neat as a theorem. Q. E. D., baby. Waterhouse strides forward

confidently, sacrificing another square centimeter of epidermis to his

ravenous shoes. As he later reconstructs it, he has, without meaning to,

interpolated himself between Mary cCmndhd and her date, and perhaps jostled

the latter's elbow and forced him to spill his drink. It is a startling move

that quiets the group. Waterhouse opens his mouth and says "Gxnn bhldh sqrd

m!"

"Hey, friend!" says Mary's date. Waterhouse turns towards the sound of

the voice. The sloppy grin draped across his face serves as a convenient

bulls eye, and Mary's date's fist homes in on it unerringly. The bottom half

of Waterhouse's head goes numb, his mouth fills with a warm fluid that

tastes nutritious. The vast concrete floor somehow takes to the air, spins

like a flipped coin, and bounces off the side of his head. All four of

Waterhouse's limbs seem to be pinned against the floor by the weight of his

torso.

Some sort of commotion is happening up on that remote plane of most

people's heads, five to six feet above the floor, where social interaction

traditionally takes place. Mary's date is being hustled off to the side by a

large powerful fellow it is hard to recognize faces from this angle, but a

good candidate would be Rod. Rod is shouting in Qwghlmian.

Actually, everyone is shouting in Qwghlmian even the ones who are

speaking in English because Waterhouse's speech recognition centers have a

bad case of jangly ganglia. Best to leave that fancy stuff for later, and

concentrate on more basic phylogenesis: it would be nice, for example, to be

a vertebrate again. After that quadrupedal locomotion might come in handy.

A perky Qwghlmian Australian fellow in an RAAF uniform steps up and

grabs his right anterior fin, jerking him up the evolutionary ladder before

he's ready. He is not doing Waterhouse a favor so much as he is getting

Waterhouse's face up where it can be better scrutinized. The RAAF fellow

shouts at him (because the music has started again):

"Where'd you learn to talk like that?"

Waterhouse doesn't know where to begin; god forbid he should offend

these people again. But he doesn't have to. The RAAF guy screws up his face

in disgust, as if he had just noticed a six foot tapeworm trying to escape

from Waterhouse's throat. "Outer Qwghlm?" he asks.

Waterhouse nods. The confused and shocked faces before him collapse

into graven masks. Inner Qwghlmians! Of course! The inner islanders are

perennially screwed, hence have the best music, the most entertaining

personalities, but are constantly being shipped off to Barbados to chop

sugar cane, or to Tasmania to chase sheep, or to well, to the Southwest

Pacific to be pursued through the jungle by starving Nips draped with live

satchel charges.

The RAAF chap forces himself to smile, chucks Waterhouse gently on the

shoulder. Someone in this group is going to have to take the unpleasant job

of playing diplomat, smoothing it all over, and with the true Inner

Qwghlmian's nose for a shit job, RAAF boy has just volunteered. "With us,"

he explains brightly, "what you just said isn't a polite greeting."

"Oh," Waterhouse says, "what did I say, then?"

"You said that while you were down at the mill to lodge a complaint

about a sack with a weak seam that sprung loose on Thursday, you were led to

understand, by the tone of the proprietor's voice, that Mary's great aunt, a

spinster who had a loose reputation as a younger woman, had contracted a

fungal infection in her toenails."

There is a long silence. Then everyone speaks at once. Finally a

woman's voice breaks through the cacophony: "No, no!" Waterhouse looks; it's

Mary. "I understood him to say that it was at the pub, and that he was there

to apply for a job catching rats, and that it was my neighbor's dog that had

come down with rabies."

"He was at the basilica for confession the priest angina " someone

shouts from the back. Then everyone talks at once: "The dockside Mary's half

sister leprosy Wednesday complaining about a loud party!"

There's a strong arm around Waterhouse's shoulders, turning him away

from all for this. He cannot turn his head to see who owns this limb,

because his vertebrae have again become unstacked. He figures out that it's

Rod, nobly taking his poor addled Yank roommate under his wing. Rod pulls a

clean hanky from his pocket and puts it up to Waterhouse's mouth, then takes

his hand away. The hanky sticks to his lip, which is now shaped like a

barrage balloon.

That's not the only decent thing he does. He even gets Waterhouse a

drink, and finds him a chair. "You know about the Navajos?" Rod asks.

"Huh?"

"Your marines use Navajo Indians as radio operators they can speak to

each other in their own language and the Nips have no idea what the fuck

they're saying."

"Oh. Yeah. Heard about that," Waterhouse says.

"Winnie Churchill heard about those Navajos. Liked the idea. Wanted His

Majesty's forces to do likewise. We don't have Navajos. But "

"You have Qwghlmians," Waterhouse says.

"There are two different programs underway," Rod says. "Royal Navy is

using Outer Qwghlmians. Army and Air Force are using Inner."

"How's it working out?"

Rod shrugs. "So so. Qwghlmian is a very pithy language. Bears no

relationship to English or Celtic its closest relatives are !Qnd, which is

spoken by a tribe of pygmies in Madagascar, and Aleut. Anyway, the pithier,

the better, right?"

"By all means," Waterhouse says. "Less redundancy harder to break the

code."

"Problem is, if it's not exactly a dead language, then it's lying on a

litter with a priest standing over it making the sign of the cross. You

know?"

Waterhouse nods.

"So everyone hears it a little differently. Like just now they heard

your Outer Qwghlmian accent, and assumed you were delivering an insult. But

I could tell you were saying that you believed, based on a rumor you heard

last Tuesday in the meat market, that Mary was convalescing normally and

would be back on her feet within a week."

"I was trying to say that she looked beautiful," Waterhouse protests.

"Ah!" Rod says. "Then you should have said, 'Gxnn bhldh sqrd m!'"

"That's what I said!"

"No, you confused the mid glottal with the frontal glottal," Rod says.

"Honestly," Waterhouse says, "can you tell them apart over a noisy

radio?"

"No," Rod says. "On the radio, we stick to the basics: 'Get in there

and take that pillbox or I'll fucking kill you.' And that sort of thing."

Before much longer, the band has finished its last set and the party's

over. "Well," Waterhouse says, "would you tell Mary what I really did mean

to say?"

"Oh, I'm sure there's no need," Rod says confidently. "Mary is a good

judge of character. I'm sure she knows what you meant. Qwghlmians excel at

nonverbal communication."

Waterhouse just barely restrains himself from saying I guess you'd have

to, which would probably just earn him another slug in the face. Rod shakes

his hand and departs. Waterhouse, marooned by his shoes, hobbles out.

Chapter 62 INRI

Goto Dengo lies on a cot of woven rushes for six weeks, under a white

cone of mosquito netting that stirs in the breezes from the windows. When

there is a typhoon, the nurses clasp mother of pearl shutters over the

windows, but mostly they are left open day and night. Outside the window, an

immense stairway has been hand carved up the side of a green mountain. When

the sun shines, the new rice on those terraces fluoresces; green light boils

into the room like flames. He can see small gnarled people in colorful

clothes transplanting rice seedlings and tinkering with the irrigation

system. The wall of his room is plain, cream colored plaster spanned with

forking deltas of cracks, like the blood vessels on the surface of an

eyeball. It is decorated only with a crucifix carved out of napa wood in

maniacal detail. Jesus's eyes are smooth orbs without pupil or iris, as in

Roman statues. He hangs askew on the crucifix, arms stretched out, the

ligaments probably pulled loose from their moorings now, the crooked legs,

broken by the butt of a Roman spear, unable to support the body. A pitted,

rusty iron nail transfixes each palm, and a third suffices for both feet.

Goto Dengo notices after a while that the sculptor has arranged the three

nails in a perfect equilateral triangle. He and Jesus spend many hours and

days staring at each other through the white veil that hangs around the bed;

when it shifts in the mountain breezes, Jesus seems to writhe. An open

scroll is fixed to the top of the crucifix; it says I.N.R.I. Goto Dengo

spends a long time trying to fathom this. I Need Rapid something? Initiate

Nail Removal Immediately?

The veil parts and a perfect young woman in a severe black and white

habit is standing in the gap, radiant in the green light coming off the

terraces, carrying a bowl of steaming water. She peels back his hospital

gown and begins to sponge him off. Goto Dengo motions towards the crucifix

and asks about it perhaps the woman has learned a little Nipponese. If she

hears him, she gives no sign. She is probably deaf or crazy or both; the

Christians are notorious for the way they dote on defective persons. Her

gaze is fixed on Goto Dengo's body, which she swabs gently but implacably,

one postage stamp sized bit at a time. Goto Dengo's mind is still playing

tricks with him, and looking down at his naked torso he gets all turned

around for a moment and thinks that he is looking at the nailed wreck of

Jesus. His ribs are sticking out and his skin is a cluttered map of sores

and scars. He cannot possibly be good for anything now; why are they not

sending him back to Nippon? Why haven't they simply killed him? "You speak

English?" he says, and her huge brown eyes jump just a bit. She is the most

beautiful woman he has ever seen. To her, he must be a loathsome thing, a

specimen under a glass slide in a pathology lab. When she leaves the room

she will probably go and wash herself meticulously and then do anything to

flush the memory of Goto Dengo's body out of her clean, virginal mind.

He drifts away into a fever, and sees himself from the vantage point of

a mosquito trying to find a way in through the netting: a haggard, wracked

body splayed, like a slapped insect, on a wooden trestle. The only way you

can tell he's Nipponese is by the strip of white cloth tied around his

forehead, but instead of an orange sun painted on it is an inscription:

I.N.R.I.

A man in a long black robe is sitting beside him, holding a string of

red coral beads in his hand, a tiny crucifix dangling from that. He has the

big head and heavy brow of those strange people working up on the rice

terraces, but his receding hairline and swept back silver brown hair are

very European, as are his intense eyes. "Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum," he

is saying. "It is Latin. Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews."

"Jew? I thought Jesus was Christian," said Goto Dengo.

The man in the black robe just stares at him. Goto Dengo tries again:

"I didn't know Jews spoke Latin."

One day a wheeled chair is pushed into his room; he stares at it with

dull curiosity. He has heard of these things they are used behind high walls

to transport shamefully imperfect persons from one room to an other.

Suddenly these tiny girls have picked him up and dropped him into it! One of

them says something about fresh air and the next thing he knows he's being

wheeled out the door and into a corridor! They have buckled him in so he

doesn't fall out, and he twists uneasily in the chair, trying to hide his

face. The girl rolls him out to a huge verandah that looks out over the

mountains. Mist rises up from the leaves and birds scream. On the wall

behind him is a large painting of I.N.R.I. chained naked to a post, shedding

blood from hundreds of parallel whip marks. A centurion stands above him

with a scourge. His eyes look strangely Nipponese.

Three other Nipponese men are sitting on the verandah. One of them

talks to himself unintelligibly and keeps picking at a sore on his arm that

bleeds continuously into a towel on his lap. Another one has had his arms

and face burned off, and peers out at the world through a single hole in a

blank mask of scar tissue. The third has been tied into his chair with many

wide strips of cloth because he flops around all the time like a beached

fish and makes unintelligible moaning noises.

Goto Dengo eyes the railing of the verandah, wondering if he can muster

the effort to wheel himself over there and fling his body over the edge. Why

has he not been allowed to die honorably?

The crew of the submarine treated him and the other evacuees with an

unreadable combination of reverence and disgust.

When was he set apart from his race? It happened long before his

evacuation from New Guinea. The lieutenant who rescued him from the

headhunters treated him as a criminal and sentenced him to execution. Even

before then, he was different. Why did the sharks not eat him? Does his

flesh smell different? He should have died with his comrades in the Bismarck

Sea. He lived, partly because he was lucky, partly because he could swim.

Why could he swim? Partly because his body was good at it but partly

because his father raised him not to believe in demons.

He laughs out loud. The other men on the verandah turn to look at him.

He was raised not to believe in demons, and now he is one.

Black robe laughs out loud at Goto Dengo during his next visit. "I am

not trying to convert you," he says. "Please do not tell your superiors

about your suspicions. We have been strictly forbidden to proselytize, and

there would be brutal repercussions."

"You aren't trying to convert me with words," Goto Dengo admits, "but

just by having me here." His English does not quite suffice.

Black robe's name is Father Ferdinand. He is a Jesuit or something,

with enough English to run rings around Goto Dengo. "In what way does merely

having you in this place constitute proselytization?" Then, just to break

Goto Dengo's legs out from under him, he says the same thing in half decent

Nipponese.

"I don't know. The art."

"If you don't like our art, close your eyes and think of the emperor."

"I can't keep my eyes closed all the time."

Father Ferdinand laughs snidely. "Really? Most of your countrymen seem

to have no difficulty with keeping their eyes tightly shut from cradle to

grave."

"Why don't you have happy art? Is this a hospital or a morgue?"

"La Pasyon is important here," says Father Ferdinand.

"La Pasyon?"

"Christ's suffering. It speaks deeply to the people of the Philippines.

Especially now."

Goto Dengo has another complaint that he is not able to voice until he

borrows Father Ferdinand's Japanese English dictionary and spends some time

working with it.

"Let me see if I understand you," Father Ferdinand says. "You believe

that when we treat you with mercy and dignity, we are implicitly trying to

convert you to Roman Catholicism."

"You bent my words again," says Goto Dengo.

"You spoke crooked words and I straightened them," snaps Father

Ferdinand.

"You are trying to make me into one of you."

"One of us? What do you mean by that?"

"A low person."

"Why would we want to do that?"

"Because you have a low person religion. A loser religion. If you make

me into a low person, it will make me want to follow that religion."

"And by treating you decently we are trying to make you into a low

person?"

"In Nippon, a sick person would not be treated as well."

"You needn't explain that to us," Father Ferdinand says. "You are in

the middle of a country full of women who have been raped by Nipponese

soldiers."

Time to change the subject. "Ignoti et quasi occulti Societas

Eruditorum," says Goto Dengo, reading the inscription on a medallion that

hangs from Father Ferdinand's neck. "More Latin? What does it mean?"

"It is an organization I belong to. It is ecumenical."

"What does that mean?"

"Anyone can join it. Even you, after you get better."

"I will get better," Goto Dengo says. "No one will know that I was

sick."

"Except for us. Oh, I understand! You mean, no Nipponese people will

know. That's true."

"But the others here will not get better."

"It is true. You have the best prognosis of any patient here."

"You are receiving those sick Nipponese men into your bosoms."

"Yes. This is more or less dictated by our religion."

"They are low people now. You want them to join your low person

religion."

"Only insofar as it is good for them," says Father Ferdinand. "It's not

like those guys are going to run out and build us a new cathedral or

something."

The next day, Goto Dengo is deemed to be cured. He does not feel cured

at all, but he will do anything to get out of this rut: losing one staredown

after another with the King of the Jews.

He expects that they will saddle him with a duffel bag and send him

down to the bus terminal to fend for himself, but instead a car comes to get

him. As if that's not good enough, the car takes him to an airfield, where a

light plane picks him up. It is the first time he has ever flown in a plane,

and the excitement revives him more than six weeks in the hospital. The

plane takes off between two green mountains and heads south (judging from

the sun's position) and for the first time he understands where he's been:

in the center of Luzon Island, north of Manila.

Half an hour later, he's above the capital, banking over the Pasig

River and then the bay, chockablock with military transports. The corniche

is guarded by a picket line of coconut palms. Seen from overhead, their

branches writhe in the sea breeze like colossal tarantulas impaled on

spikes. Looking over the pilot's shoulder, he sees a pair of paved airstrips

in the flat paddy land just south of the city, crossing at an acute angle to

form a narrow X. The light plane porpoises through gusts. It bounces down

the airstrip like an overinflated soccer ball, taxiing past most of the

hangars and finally fishtailing to a stop near an isolated guard hut where a

man waits on a motorcycle with an empty sidecar. Goto Dengo is directed out

of the plane and into the sidecar by means of gestures; no one will speak to

him. He is dressed in an Army uniform devoid of rank and insignia.

A pair of goggles rests on the seat, and he puts them on to keep the

bugs out of his eyes. He is a little nervous because he does not have papers

and he does not have orders. But they are waved out of the airbase and onto

the road without any checks.

The motorcycle driver is a young Filipino man who keeps grinning

broadly, at the risk of getting insects stuck between his big white teeth.

He seems to think that he has the best job in the whole world, and perhaps

he does. He turns south onto a road that probably qualifies as a big highway

around these parts, and commences weaving through traffic. Most of this is

produce carts drawn by carabaos big oxlike things with imposing crescent

moon shaped horns. There are a few automobiles, and the occasional military

truck.

For the first couple of hours the road is straight, and runs across

damp table land used for growing rice. Goto Dengo catches glimpses of a body

of water off to the left, and isn't sure whether it is a big lake or part of

the ocean. "Laguna de Bay," says the driver, when he catches Goto looking at

it. "Very beautiful."

Then they turn away from the lake onto a road that climbs gently into

sugar cane territory. Suddenly, Goto Dengo catches sight of a volcano: a

symmetrical cone, black with vegetation, cloaked in mist as though protected

by a mosquito net. The sheer density of the air makes it impossible to judge

size and distance; it could be a little cinder cone just off the road, or a

huge stratovolcano fifty miles away.

Banana trees, coconut palms, oil palms, and date palms begin to appear,

sparsely at first, transforming the landscape into a kind of moist savannah.

The driver pulls into a shambolic roadside store to buy petrol. Goto Dengo

unfolds his jangled body from the sidecar and sits down at a table beneath

an umbrella. He wipes a crust of sweat and dirt from his forehead with the

clean handkerchief that he found in his pocket this morning, and orders

something to drink. They bring him a glass of ice water, a bowl of raw,

locally produced sugar, and a plate of pinball sized calamansi limes. He

squeezes the calamansis into the water, stirs in sugar, and drinks it

convulsively.

The driver comes and joins him; he has cadged a free cup of water from

the proprietors. He always wears a mischievous grin, as if he and Goto Dengo

are sharing a little private joke. He raises an imaginary rifle to his face

and makes a scratching motion with his trigger finger. "You soldier?"

Goto Dengo thinks it over. "No," he says, "I do not deserve to call

myself a soldier."

The driver is astonished. "No soldier? I thought you were soldier. What

are you?"

Goto Dengo thinks about claiming that he is a poet. But he does not

deserve that title either. "I am a digger," he finally says, "I dig holes."

"Ahh," the driver says, as if he understands. "Hey, you want?" He takes

two cigarettes out of his pocket.

Goto Dengo has to laugh at the smoothness of the gambit. "Over here,"

he says to the proprietor. "Cigarettes." The driver grins and puts his

cigarettes back where they came from.

The owner comes over and hands Goto Dengo a pack of Lucky Strikes and a

book of matches. "How much?" says Goto Dengo, and takes out an envelope of

money that he found in his pocket this morning. He takes the bills out and

looks at them: each is printed in English with the words THE JAPANESE

GOVERNMENT and then some number of pesos. There is a picture of a fat

obelisk in the middle, a monument to Jose P. Rizal that stands near the

Manila Hotel.

The proprietor grimaces. "You have silver?"

"Silver? Silver metal?"

"Yes," the driver says.

"Is that what people use?" The driver nods.

"This is no good?" Goto Dengo holds up the crisp, perfect bills.

The owner takes the envelope from Goto Dengo's hand and counts out a

few of the largest denomination of bills, pockets them, and leaves.

Goto Dengo breaks the seal on the pack of Lucky Strikes, raps the pack

on the tabletop a few times, and opens the lid. In addition to the

cigarettes, there is a printed card in there. He can just see the top part

of it: it is a drawing of a man in a military officer's cap. He pulls it out

slowly, revealing an eagle insignia on the cap, a pair of aviator

sunglasses, an enormous corncob pipe, a lapel bearing a line of four stars,

and finally, in block letters, the words I SHALL RETURN.

The driver is looking purposefully nonchalant. Goto Dengo shows him the

card and raises his eyebrows. "It is nothing," the driver says. "Japan very

strong. Japanese people will be here forever. MacArthur good only for

selling cigarettes."

When Goto Dengo opens the book of matches, he finds the same picture of

MacArthur, and the same words, printed on the inside.

After a smoke, they are back on the road. More black cones coalesce,

all around them now, and the road begins to ramble up over hills and down

into valleys. The trees get closer and closer together until they are riding

through a sort of cultivated and inhabited jungle: pineapples close to the

ground, coffee and cocoa bushes in the middle, bananas and coconuts

overhead. They pass through one village after another, each one a cluster of

dilapidated huts huddled around a great white church, built squat and strong

to survive earthquakes. They zigzag around heaps of fresh coconuts piled by

the roadside, spilling out into the right of way. Finally they turn off of

the main road and into a dirt track that winds through the trees. The track

has been rutted by the tires of trucks that are much too big for it. Freshly

snapped off tree branches litter the ground.

They pass through a deserted village. Stray dogs flit in and out of

huts whose front doors swing unlatched. Heaps of young green coconuts rot

under snarls of black flies.

Another mile down the road, the cultivated forest gives way to the wild

kind, and a military checkpoint bars the road. The smile vanishes from the

driver's face.

Goto Dengo states his name to one of the guards. Not knowing why he is

here, he can say nothing else. He is pretty sure now that this is a prison

camp and that he is about to become an inmate. As his eyes adjust he can see

a barrier of barbed wire strung from tree to tree, and a second barrier

inside of that. Peering carefully into the undergrowth he can make out where

they dug bunkers and established pillboxes, he can map out their

interlocking fields of fire in his mind. He sees ropes dangling from the

tops of tall trees where snipers can tie themselves into the branches if

need be. It has all been done according to doctrine, but it has a perfection

that is never seen on a real battlefield, only in training camps.

He is startled to realize that all of these fortifications are designed

to keep people out, not keep them in.

A call comes through on the field telephone, the barrier is raised, and

they are waved through. Half a mile into the jungle they come to a cluster

of tents pitched on platforms made from the freshly hewn logs of the trees

that were cut down to make this clearing. A lieutenant is standing in a

shady patch, waiting for them.

"Lieutenant Goto, I am Lieutenant Mori."

"You have arrived in the Southern Resource Zone recently, Lieutenant

Mori?"

"Yes. How did you know?"

"You are standing directly beneath a coconut tree."

Lieutenant Mori looks straight up in the air to see several wooly brown

cannonballs dangling high over his head. "Ah, so!" he says, and moves out of

the way. "Did you have any conversation with the driver on the way here?"

"Just a few words."

"What did you discuss with him?"

"Cigarettes. Silver."

"Silver?" Lieutenant Mori is very interested in this, so Goto Dengo

recounts their whole conversation.

"You told him that you were a digger?"

"Something like that, yes."

Lieutenant Mori backs off a step, turning to an enlisted man who has

been standing off to the side, and nods. The enlisted man picks the butt of

his rifle up off the ground, wheels the weapon around to a horizontal

position, and turns towards the driver. He covers the distance in about six

steps, accelerating to a full sprint, and cuts loose with a throaty roar as

he drives his bayonet into the driver's slim body. The victim is picked up

off his feet, then sprawls on his back with a low gasp. The soldier

straddles him and thrusts the bayonet into his torso several more times,

each stroke making a wet hissing sound as metal slides between walls of

meat.

The driver ends up sprawled motionless on the ground, jetting blood in

all directions.

"The indiscretion will not be held against you," says Lieutenant Mori

brightly, "because you did not know the nature of your new assignment.

"Pardon me?"

"Digging. You are here to dig, Goto san." He snaps to attention and

bows deeply. "Let me be the first to congratulate you. Your assignment is a

very important one."

Goto Dengo returns the bow, not sure how deep to make it. "So I'm not "

He gropes for words. In trouble? A pariah? Condemned to death? "I'm not a

low person here?"

"You are a very high person here, Goto san. Please come with me."

Lieutenant Mori gestures towards one of the tents.

As Goto Dengo walks away, he hears the young motorcycle driver mumble

something.

"What did he say?" Lieutenant Mori asks.

"He said, 'Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.' It's a

religious thing," Goto Dengo explains.

Chapter 63 CALIFORNIA

Half of the people who work at SFO, San Francisco International

Airport, now seem to be Filipino, which certainly helps to ease the shock of

reentry. Randy gets singled out, as he always does, for a thorough luggage

search by the exclusively Anglo customs officials. Men traveling by

themselves with practically no luggage seem to irritate the American

authorities. It's not so much that they think you are a drug trafficker as

that you fit, in the most schematic possible way, the profile of the most

pathologically optimistic conceivable drug trafficker, and hence practically

force them to investigate you. Irritated that you have forced their hand in

this manner, they want to teach you a lesson: travel with a wife and four

kids next time, or check a few giant trundling bags, or something, man! What

were you thinking? Never mind that Randy is coming in from a place where

DEATH TO DRUG TRAFFICKERS is posted all over the airport the way CAUTION:

WET FLOOR is here.

The most Kafkaesque moment is, as always, when the customs official

asks what he does for a living, and he has to devise an answer that will not

sound like the frantic improvisations of a drug mule with a belly full of

ominously swelling heroin stuffed condoms. "I work for a private

telecommunications provider" seems to be innocuous enough. "Oh, like a phone

company?" says the customs official, as if she's having none of it. "The

phone market isn't really that available to us," Randy says, "so we provide

other communications services. Mostly data."

"Does that involve a lot of traveling around from place to place then?"

asks the customs official, paging through the luridly stamped back pages of

Randy's passport. She makes eye contact with a more senior customs official

who sidles over towards them. Randy now feels himself getting nervous,

exactly the way your drug mule would, and fights the impulse to scrub his

damp palms against his pant legs, which would probably guarantee him a trip

through the magnetic tunnel of a CAT scanner, a triple dose of mint flavored

laxative, and several hours of straining over a stainless steel evidence

bucket. "Yes, it does," Randy says.

The senior customs official, trying to be unobtrusive and low key in a

way that makes Randy stifle a sort of gasping, pained outburst of laughter,

begins to flip through some appalling communications industry magazine that

Randy stuffed into his briefcase on his way out the door back in Manila. The

word INTERNET appears at least five times on the front cover. Randy stares

directly into the eyes of the female customs official and says, "The

Internet." Totally factitious understanding dawns on the woman's face, and

her eyes ping bosswards. The boss, still deeply absorbed in an article about

the next generation of high speed routers, shoves out his lower lip and

nods, like every other nineties American male who senses that knowing this

stuff is now as intrinsic to maleness as changing flat tires was to Dad. "I

hear that's really exciting now," the woman says in a completely different

tone of voice, and begins scooping Randy's stuff together into a big pile so

that he can repack it. Suddenly the spell is broken, Randy is a member in

good standing of American society again, having cheerfully endured this

process of being ritually goosed by the Government. He feels a strong

impulse to drive straight to the nearest gun store and spend about ten

thousand dollars. Not that he wants to hurt anyone; it's just that any kind

of government authority gives him the creeps now. He's probably been hanging

out too much with the ridiculously heavily armed Tom Howard. First a

hostility to rainforests, now a desire to own an automatic weapon; where is

this all going?

Avi is waiting for him, a tall pale figure standing at the velvet rope

surrounded by hundreds of Filipinas in a state of emotional riot,

brandishing gladiola spears like medieval pikemen. Avi has his hands in the

pockets of his floor skimming coat, and keeps his head turned in Randy's

direction but is sort of concentrating on a point about halfway between

them, frowning in an owlish way. This is the same frown that Randy's

grandmother used to wear when she was teasing apart a tangle of string from

her junk drawer. Avi adopts it when he is doing basically the same thing to

some new complex of information. He must have read Randy's e mail message

about the gold. It occurs to Randy that he missed a great opportunity for a

practical joke: he could have loaded up his bag with a couple of lead bricks

and then handed it to Avi and completely blown his mind. Too late. Avi

rotates around his vertical axis as Randy comes abreast of him and then

breaks into a stride that matches Randy's pace. There is some unarticulated

protocol that dictates when Randy and Avi will shake hands, when they will

hug, and when they will just act like they've only been separated for a few

minutes. A recent exchange of e mail seems to constitute a virtual reunion

that obviates any hand shaking or hugging. "You were right about the cheesy

dialog," is the first thing Avi says. "You're spending too much time with

Shaftoe, seeing things his way. This was not an attempt to send you a

message, at least not in the way Shaftoe means."

"What's your interpretation, then?"

"How would you go about establishing a new currency?" Avi asks.

Randy frequently overhears snatches of business related conversation

from people he passes in airports, and it's always about how did the big

presentation go, or who's on the short list to replace the departing CFO, or

something. He prides himself on what he believes to be the much higher

plane, or at least the much more bizarre subject matter, of his interchanges

with Avi. They are walking together around the slow arc of SFO's inner ring.

A whiff of soy sauce and ginger drifts out of a restaurant and fogs Randy's

mind, making him unsure, for a moment, which hemisphere he's in.

"Uh, it's not something I have given much thought to," he says. "Is

that what we are about now? Are we going to establish a new currency?"

"Well obviously someone needs to establish one that doesn't suck," Avi

says.

"Is this some exercise in keeping a straight face?" Randy asks.

"Don't you ever read the newspapers?" Avi grabs Randy by the elbow and

drags him over towards a newsstand. Several papers are running front page

stories about crashing Southeast Asian currencies, but this isn't all that

new.

"I know currency fluctuations are important to Epiphyte," Randy says.

"But my god, it's so tedious I just want to run away.

"Well, it's not tedious to her," Avi says, yanking out three different

newspapers that have all decided to run the same wire service photograph: an

adorable Thai moppet standing in a mile long queue in front of a bank,

holding up a single American dollar bill.

"I know it's a big deal for some of our customers," Randy says, "I just

didn't really think of it as a business opportunity."

"No, think about it," Avi says. He counts out a few dollar bills of his

own to pay for the newspapers, then swerves towards an exit. They enter a

tunnel that leads to a parking garage. "The sultan feels that "

"You've been just sort of hanging out with the sultan?"

"Mostly with Pragasu. Will you let me finish? We decided to set up the

Crypt, right?"

"Right."

"What is the Crypt? Do you remember its original stated function?"

"Secure, anonymous, unregulated data storage. A data haven."

"Yeah. A bit bucket. And we envisioned many applications for this."

"Boy, did we ever," Randy says, remembering many long nights around

kitchen tables and hotel rooms, writing versions of the business plan that

are now as ancient and as lost as the holographs of the Four Gospels.

"One of these was electronic banking. Heck, we even predicted it might

be one of the major applications. But whenever a business plan first makes

contact with the actual market the real world suddenly all kinds of stuff

becomes clear. You may have envisioned half a dozen potential markets for

your product, but as soon as you open your doors, one just explodes from the

pack and becomes so instantly important that good business sense dictates

that you abandon the others and concentrate all your efforts."

"And that's what happened with the e banking thing," Randy says.

"Yes. During our meetings at the Sultan's Palace," Avi says. "Before

those meetings, we envisioned well you know what we envisioned. What

actually happened was that the room was packed with these guys who were

exclusively interested in the e banking thing. That was our first clue.

Then, this!" He holds up his newspapers, whacks the dollar brandishing

moppet with the back of his hand. "So, that's the business we're in now."

"We are bankers," Randy says. He will have to keep saying this to

himself for a while in order to believe it, like, "We are striving with all

our might to uphold the goals of the 23rd Party Congress." We are bankers.

We are bankers.

"Banks used to issue their own currencies. You can see these old

banknotes in the Smithsonian. 'First National Bank of South Bumfuck will

remit ten pork bellies to the bearer,' or whatever. That had to stop because

commerce became nonlocal you needed to be able to take your money with you

when you went out West, or whatever."

"But if we're online, the whole world is local," Randy says.

"Yeah. So all we need is something to back the currency. Gold would be

good."

"Gold? Are you joking? Isn't that kind of old fashioned?"

"It was until all of the unbacked currencies in Southeast Asia went

down the toilet."

"Avi, so far I am still kind of confused, frankly. You seem to be

working your way around to telling me that my little trip to see the gold in

the jungle was no coincidence. But how can we use that gold to back our

currency?"

Avi shrugs as if it's such a minor detail he hasn't even bothered to

think about it. "That's just a deal making issue."

"Oh, god."

"These people who sent you a message want to get into business with us.

Your trip to see the gold was a credit check."

They are walking through a tunnel toward the garage, stuck behind an

extended clan of Southeast Asians in elaborate headdresses. Perhaps the

entire remaining gene pool of some nearly extinct mountain dwelling minority

group. Their belongings are in giant boxes wrapped in iridescent pink

synthetic twine, balanced atop airport luggage carts.

"A credit check." Randy always hates it when he gets so far behind Avi

that all he can do is lamely repeat phrases.

"You know how, when you and Charlene bought that house, the lender had

to look at it first?"

"I bought it for cash."

"Okay, okay, but in general, before a bank will issue a mortgage on a

house, they will inspect it. Not in great detail, necessarily. They'll just

have some executive of the bank drive by the property to verify that it

exists and is where the documents claim it is, and so on.

"So, that's what my journey to the jungle was about?"

"Yeah. Some of the potential, uh, participants in the project just

wanted to make it clear to us that they were, in fact, in possession of this

gold."

"I really have to wonder what 'possession' denotes in this case."

"Me too," Avi says. "I've been sort of puzzling over that one." Hence,

Randy thinks, the frowny look in the airport.

"I just thought they wanted to sell it," Randy says.

"Why? Why sell it?"

"To liquidate it. So they could buy real estate. Or five thousand pairs

of shoes. Or something."

Avi scrunches his face in disappointment. "Oh, Randy, that is really

unworthy, alluding to the Marcoses. The gold you saw is pocket change

compared to what Ferdinand Marcos dug up. The people who set up your trip to

the jungle are satellites of satellites of him."

"Well. Consider it a cry for help," Randy says. "Words seem to be

passing back and forth between us, but I understand less and less."

Avi opens his mouth to respond, but just then the animists trigger

their car alarm. Unable to propitiate it, they form a circle around the car

and grin at one another. Avi and Randy pick up their pace and get well away

from it.

Avi stops and straightens, as if pulled up short. "Speaking of not

understanding things," he says, "you need to communicate with that girl. Amy

Shaftoe."

"Has she been communicating with you?"

"In the course of twenty minutes' phone conversation, she has deeply

and eternally bonded with Kia," Avi says.

"I would believe that without hesitation."

"It wasn't even like they got to know each other. It was like they knew

each other in a previous life and had just gotten back in touch."

"Yeah. So?"

"Kia now feels bound by duty and honor to present a united front with

America Shaftoe."

"It all hangs together," Randy says.

"Acting sort of like Amy's emotional agent or lawyer, she has made it

clear to me that we, Epiphyte Corporation, owe Amy our full attention and

concern."

"And what does Amy want?"

"That was my question," Avi says, "and I was made to feel very bad for

asking it. Whatever it is that we that you owe to Amy is something so

obvious that merely manifesting a need to verbalize it is... just...

really..."

"Shabby. Insensitive."

"Coarse. Brutish."

"A really transparent, toddler level exercise in the cheapest kind of,

of. . ."

"Of evasion of personal responsibility for one's own gross misdeeds."

"Kia was rolling her eyes, I imagine. Her lip was sort of curled."

"She drew breath as if to give me a good piece of her mind but then

thought better of it."

"Not because you're her boss. But because you would never understand."

"This is just one of those evils that has to be sort of accepted and

swallowed, by any mature woman who's been around the block."

"Who knows the harsh realities. Yeah," Randy says.

"Okay, you can tell Kia that her client's needs and demands have been

communicated to the guilty party "

"Have they?"

"Tell her that the fact that her client has needs and demands has been

heavy handedly insinuated to me and that it is understood that the ball is

in my court."

"And we can stand down to some kind of detente while a response is

prepared?"

"Certainly. Kia can return to her normal duties for the time being."

"Thank you, Randy."

Avi's Range Rover is parked in the most remote part of the roof of the

parking ramp, in the center of about twenty five empty parking spaces that

form a sort of security buffer zone. When they have traversed about half of

the glacis, the car's headlights flutter, and Randy hears the preparatory

snap of a sound system being energized. "The Range Rover has picked us up on

Doppler radar," Avi says hastily.

The Range Rover speaketh in a fearsome Oz like voice cranked up to

burning bush decibel levels. "You are being tracked by Cerberus! Please

alter your course immediately!"

"I can't believe you bought one of these things," Randy says.

"You have encroached on the Cerberus defensive perimeter! Move back.

Move back," says the Range Rover. "An armed response team is being placed on

standby."

"It is the only cryptographically sound car alarm system," Avi says, as

if that settles the matter. He digs out a keychain attached to a black

polycarbonate fob with the same dimensions, and number of buttons, as a

television remote control. He enters a long series of digits and cuts off

the voice in the middle of proclaiming that Randy and Avi are being recorded

on a digital video camera that is sensitive into the near infra red range.

"Normally it doesn't do that," Avi says. "I had it set to its maximum

alert status."

"What's the worst that could happen? Someone would steal your car and

the insurance company would buy you a new one?"

"I couldn't care less if it gets stolen. The worst that could happen

would be a car bomb, or, not quite as bad, someone putting a bug in my car

and listening to everything I say."

Avi drives Randy over the San Andreas Fault to his place in Pacifica,

which is where Randy stores his car while he's overseas. Avi's wife Devorah

is in at the doctor's for a routine prenatal and all the kids are either at

school or being hustled around the neighborhood by their tag team duo of

tough Israeli nannies. Avi's nannies have the souls of war hardened Soviet

paratroopers in the bodies of nubile eighteen year old girls. The house has

been utterly abandoned to kid raising. The formal dining room has been

converted to a nanny barracks with bunk beds hammered together from

unfinished two by fours, the parlor filled with cribs and changing tables,

and every square centimeter of cheap shag carpet in the place has been

infused with a few dozen flakes of glitter, in various festive colors, which

if they even cared about getting rid of it could only be removed through

direct microsurgical extraction, one flake at a time. Avi plies Randy with a

sandwich of turkey bologna and ketchup on generic Wonderoid bread. It is

still too early in Manila for Randy to call Amy and make amends for whatever

he did wrong. Down below them, in Avi's basement office, a fax machine

shrieks and rustles like a bird in a coffee can. A laminated CIA map of

Sierra Leone is spread out on the table, peeking out here and there through

numerous overlying strata of dirty dishes, newspapers, coloring books, and

drafts of the Epiphyte(2) Business Plan. Post it notes are stuck to the map

from place to place. Written on each note, in Avi's distinctive triple ought

Rapidograph drafting pen hand, is a latitude and longitude with lots of

significant digits, and some kind of precis of what happened there: "5

women, 2 men, 4 children, with machetes photos:" and then serial numbers

from Avi's database.

Randy was a little groggy on the drive over, and was irritable about

the inappropriate daylight, but after the sandwich his metabolism tries to

get into the spirit of things. He has learned to surf these mysterious

endocrinological swells. "I'm going to get going," he says, and stands.

"Your overall plan, again?"

"First I go south," Randy says, superstitiously not even wanting to

utter the name of the place where he used to live. "For no more than a day,

I hope. Then jet lag will land on me like a plunging safe and I will hole up

somewhere and watch basketball through the vee of my feet for maybe a day.

Then I head north to the Palouse country."

Avi raises his eyebrows. "Home?"

"Yeah."

"Hey, before I forget could you look for information on the Whitmans

while you're up there?"

"You mean the missionaries?"

"Yeah. They came out to the Palouse to convert the Cayuse Indians, who

were these magnificent horsemen. They had the best of intentions, but they

accidentally gave them measles. Annihilated the whole tribe."

"Does that really land within the boundaries of your obsession?

Inadvertent genocide?"

"Anomalous cases have heightened utility in that they help us delineate

the boundaries of the field."

"I'll see what I can find about the Whitmans."

"May I inquire," Avi says, "why you are going up there? Family visit?"

"My grandmother is moving to a managed care facility. Her children are

convening to divide up her furniture and so on, which I find a little

ghoulish, but it's nobody's fault and it has to be done."

"And you are going to participate?"

"I am going to avoid it as much as I can, because it's probably going

to be a catfight. Years from now, family members will still not be speaking

to each other because they didn't get Mom's Gomer Bolstrood credenza."

"What is it with Anglo Saxons and furniture? Could you explain that to

me?"

"I am going because we found a piece of paper in a briefcase in a

sunken Nazi submarine in the Palawan Passage that says, 'WATERHOUSE LAVENDER

ROSE.'"

Avi looks baffled now, in a way that Randy finds satisfying. He gets up

and climbs into his car and starts driving south, down the coast, the slow

and beautiful way.

Chapter 64 ORGAN

Lawrence Waterhouse's libido is suppressed for about a week by the pain

and swelling in his jaw. Then the pain and swelling in his groin surges into

the fore, and he begins searching his memories of the dance, wondering if he

made any progress with Mary cCmndhd.

He wakes up suddenly at four o'clock one Sunday morning, clammily

coated from his nipples to his knees. Rod is still sleeping soundly, thank

god, and so if Waterhouse did any moaning or calling out of names during his

dream, Rod's probably not aware of it. Waterhouse begins trying to clean

himself off without making a lot of noise. He doesn't even want to think

about how he's going to explain the condition of the sheets to Who Will

Launder Them. "It was completely innocent, Mrs. McTeague. I dreamed that I

came downstairs in my pajamas and that Mary was sitting in the parlor in her

uniform, drinking tea, and she turned and looked me in the eye, and then I

just couldn't control myself and aaaaAAAHHH! HUH! HUH! HUH! HUH! HUH! HUH!

HUH! HUH! HUH! HUH! HUH! And then I woke up and just look at the mess.

Mrs. McTeague (and other old ladies like her all around the world) does

the laundry only because it is her role in the giant Ejaculation Control

Conspiracy which, as Waterhouse is belatedly realizing, controls the entire

planet. No doubt she has a clipboard down in the cellar, next to her mangle,

where she marks down the frequency and volume of the ejaculations of her

four boarders. The data sheets are mailed into some Bletchley Park type of

operation somewhere (Waterhouse guesses it's disguised as a large convent in

upstate New York), where the numbers from all round the world are tabulated

on Electrical Till Corporation machines and printouts piled up on carts that

are wheeled into the offices of the high priestesses of the conspiracy,

dressed in heavily starched white raiments, embroidered with the emblem of

the conspiracy: a penis caught in a mangle. The priestesses review the data

carefully. They observe that Hitler still isn't getting any, and debate

whether letting him have some would calm him down a little bit or just give

him license to run further out of control. It will take months for the name

of Lawrence Pritchard Waterhouse to come to the top of the list, and months

for orders to be sent out to Brisbane and even then, the orders may condemn

him to another year of waiting for Mary cCmndhd to show up in his dreams

with a teacup.

Mrs. McTeague, and other ECC members (such as Mary cCmndhd and

basically all of the other young women) are offended by easy girls,

prostitutes, and whorehouses, not for religious reasons, but because they

provide a refuge where men can have ejaculations that are not controlled,

metered, or monitored in any way. Prostitutes are turncoats, collaborators.

All of this comes into Waterhouse's mind as he lies in his damp bed

between four and six o'clock in the morning, considering his place in the

world with the crystalline clarity that can only be obtained by getting a

good night's sleep and then venting several weeks' jism production. He has

reached a fork in the road.

Last night, before Rod turned in, he shined his shoes, explaining that

tomorrow morning he had to be up bright and early for church. Now,

Waterhouse knows what that means, having spent many a Sabbath on Qwghlm,

cringing and blushing under the glares of the locals, who were outraged that

he appeared to be running the huffduff equipment on the day of rest. He has

seen them shuffling into their morbid, thousand year old black stone chapel

on Sunday mornings for their three hour services. Hell, Waterhouse even

lived in a Qwghlmian chapel for several months. Its gloom suffused his whole

being.

Going to church with Rod would mean giving in to the ECC, becoming

their minion. The alternative is the whorehouse.

Even though he grew up in churches, raised by church people, Waterhouse

(as must be obvious by this point) never really understood their attitudes

about sex. Why did they get so hung up on that one issue, when there were

others like murder, war, poverty, and pestilence?

Now, finally, he gets it: the churches are merely one branch of the

ECC. And what they are doing, when they fulminate about sex, is trying to

make sure that all the young people fall in line with the ECC's program.

So, what is the end result of the ECC's efforts? Waterhouse stares at

the ceiling, which is starting to become fuzzily visible as the sun rises in

the west, or the north, or wherever the hell it rises here in the Southern

Hemisphere. He takes a quick inventory of the world and finds that basically

the ECC is running the entire planet, good countries and bad countries

alike. That all successful and respected men are minions of the ECC, or at

least are so scared of it that they pretend to be. Non ECC members live on

the fringes of society, like prostitutes, or have been driven deep

underground and must waste tremendous amounts of time and energy keeping up

a false front. If you knuckle under and become a minion of the ECC, you get

to have a career, a family, kids, wealth, house, pot roasts, clean laundry,

and the respect of all the other ECC minions. You have to pay dues in the

form of chronic nagging sexual irritation which can only be relieved by, and

at the discretion and convenience of, one person, the person designated for

this role by the ECC: your wife. On the other hand, if you reject the ECC

and its works, you can't, by definition, have a family, and your career

options are limited to pimp, gangster, and forty year enlisted sailor.

Hell, it's not even that bad of a conspiracy. They build churches and

universities, educate kids, install swingsets in parks. Sometimes they throw

a war and kill ten or twenty million people, but it's a drop in the bucket

compared to stuff like influenza which the ECC campaigns against by nagging

everyone to wash their hands and cover their mouths when sneezing.

The alarm clock. Rod rolls out of bed like it's a Nip air raid.

Waterhouse stares at the ceiling for another few minutes, dithering. But he

knows where he's going, and there's no point in wasting any more time. He's

going to church, and not exactly because he has renounced Satan and all his

works, but because he wants to fuck Mary. He almost can't help flinching

when he says (to himself) this terrible sounding thing. But the weird thing

about church is that it provides a special context within which it is

perfectly okay to want to fuck Mary. As long as he goes to church, he can

want to fuck Mary as much as he wants, he can spend all of his time, in and

out of church, thinking about fucking Mary. He can let her know that he

wants to fuck her as long as he finds a more oblique way of phrasing it. And

if he jumps through certain hoops (hoops of gold) he can even fuck Mary in

actuality, and it will all be perfectly acceptable at no time will he have

to feel the slightest trace of shame or guilt.

He rolls out of bed, startling Rod, who (being some sort of jungle

commando) is easily startled. "I'm going to fuck your cousin until the bed

collapses into a pile of splinters," Waterhouse says.

Actually, what he says is "I'm going to church with you." But

Waterhouse, the cryptologist, is engaging in a bit of secret code work here.

He is using a newly invented code, which only he knows. It will be very

dangerous if the code is ever broken, but this is impossible since there is

only one copy, and it's in Waterhouse's head. Turing might be smart enough

to break the code anyway, but he's in England, and he's on Waterhouse's

side, so he'd never tell

A few minutes later, Waterhouse and cCmndhd go downstairs, headed for

"church," which in Waterhouse's secret code, means "headquarters of the Mary

fucking campaign of 1944."

As they step out into the cool morning air they can hear Mrs. McTeague

bustling into their bedroom to strip their beds and inspect their sheets.

Waterhouse smiles, thinking that he has just gotten away with something; the

damning and overwhelming evidence found on his bed linens will be neatly